Employer liability OPS (painter's disease) employee

Supreme Court 5 March 2010

An employee joined Hunter Douglas ('HD') in 1988 at the age of 23. Among other things, HD manufactures aluminium slats (Luxaflex). The employee was working as an operator in the Coil Coating department. In the department, aluminium strips are painted and dried in so-called coil coating machines. The employee's duties included setting and assembling the paint rollers from the paint machines and cleaning them during colour changes. A climate control system was installed in the department and a local exhaust system was placed above each paint machine.

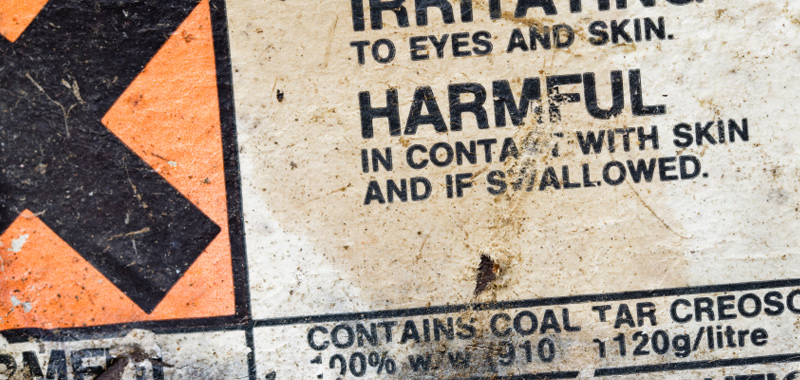

In March 1999, the employee left work due to disability discontinued: there were liver function disorders, complaints of fatigue, forgetfulness, quick irritability and gloom. In March 2000, he was eligible for WAO benefits at a disability level of 80-100%, downgraded to 55%-65% in 2005. The employee held HD liable for his health injuries due to exposure to the solvents anarcoat, thinner and acetone.

The Rotterdam subdistrict court and later the Hague Court of Appeal concluded that the employee had made it sufficiently plausible that he was suffering from health complaints that may have been caused by exposure to organic substances and solvents. Referring to reports by the Solvent team of the Netherlands Centre for Occupational Diseases and medical literature, the employee claimed that he developed a pathology that may have been caused by handling organic substances and solvents that he was required to use in his work. HD acknowledged that the employee worked with organic substances and solvents. While HD has denied that this led to exposure to these substances in concentrations dangerous to health, it has not refuted that the employee was diagnosed with a severe hepatic impairment likely to be related to exposure to solvents at work. It is therefore difficult to understand HD's insistence that there were no hazardous concentrations. The Solvent team, an interdisciplinary team with pre-eminent expertise in OPS, has deemed it likely (also given the progression of symptoms after the cessation of exposure) that the employee suffers from OPS.

The court then considered that the employee's alleged causal link between exposure to the health-related hazardous substances and his health complaints should be assumed if the employer failed to take (reasonably necessary) safety measures. The court concluded that HD did not take these safety measures. In that context, it considered that HD could be expected to take not only technical measures (extraction and paint masters) but also organisational measures, such as providing information on risks, a clean working method (without unnecessary spilling of paint and without (too) extensive use of solvents when removing spilt paint) and the use of protective equipment as well as supervising the use of the correct protective equipment. The court found that there was no evidence that such measures were taken. In its recent ruling, the Supreme Court upheld this judgment of the court.

Tip: Through the network of experts with whom Labour Injury Lawyers contact maintains, victims with work-related health injuries can find out about the feasibility of a personal injury claim.